Notes on "An Observation on Generalization"

Diving into “An Observation on Generalization”, a talk by Ilya Sutskever at the Large Language Models and Transformers Workshop, Simons Institute, 2023.

Ilya Sutskever, one of the Co-founders of OpenAI, recently gave a talk at the Large Language Models and Transformers Workshop, Simons Institute, 2023. The talk was recorded, and is available on YouTube. The topic of the talk was “An Observation on Generalization”, and Ilya talks about how we can reason about unsupervised learning using the lens of compression theory. I found the talk to be very insightful, however, it can be hard to follow at times and harder to keep the bigger picture in mind, atleast for someone like me (endowed with a less powerful cerebral cortex). Unfortunately, this was one of the few talks in the workshop that did not have an accompanying paper that went into more details. I felt that this was a good opportunity to write down my notes from the talk. Given how brilliantly Ilya put forth his theory, it was hard to really explain and present things differently. I have thus firstly transcribed the talk, and then added my own notes to provide better context or more information for clarity.

An Observation on Generalization

The talk is about really trying to understand why unsupervised learning works at all, and reason about it mathematically. To get there, Ilya first brings up the concept of learning itself (learning from data) and why machine learning works. The expectation here is that data has regularity, and machine learning models are expected to learn this regularity in our data. Bringing up the topic of supervised learning, he puts up this equation:

Low training error + more training data than “degrees of freedom” = Low test error

Now, with unsupervised learning, the dream is that given all this unlabelled data (images, text chunks, etc) we expect a machine learning model to discover this “true”, hidden structure in the data. A key point with unsupervised learning is that we typically optimize a proxy objective (next work prediction or reconstruction) while we care about a different objective (learning hidden patterns in your data to do some sequence classification, perhaps). Why should this work?

Unsupervised learning via distribution matching

To get there, we first visit distribution matching. Consider two data sources

In our above example, this is:

There have been a number of methods proposed previously (A relevant example: unsupervised machine translation) that show that this can work even for high dimensional

How can we reason about unsupervised learning now, with this background in mind?

Compression theory

Quoting Ilya here:

There is a one-to-one correspondence between all compressors and all predictors

At first glance, this statement is not obvious at all! I think there can be an entire article on just this statement, but to really give an intuitive (and, unfortunately, qualitative) answer:

Consider the case of compressing a PNG file. The more predictable the pixel patterns in the image, the lesser the amount of truly unique information contained across pixels, the better you can compress it. Another example that I found helpful was from Xiaoyu He’s talk on prediction and compression posted on LessWrong:

Let’s say you are trying to find an encoding for a string, where each character can only be “a”, “b”, “c” or “d”. Consider the string “abaaabaacbabaaabcd”. let’s take the simple encoding scheme below:

| Char | Encoding |

|---|---|

| a | 00 |

| b | 01 |

| c | 10 |

| d | 11 |

Number of bits needed for the above string: 36 bits. Suppose that all the strings in our data have the following characteristics: “a"s appear the most frequent, while “c"s and “d"s apear rarely (this is roughly the case with our anecdotal example). Thus, you can use the modified encoding scheme below:

| Char | Encoding |

|---|---|

| a | 0 |

| b | 10 |

| c | 110 |

| d | 111 |

Number of bits needed for the string: 29 bits. By being able to better predict the next character for each string, we’re able to better compress the string.

Now, with that in mind, let’s come back to the original discussion on unsupervised learning. In unsupervised learning, atleast in the realm of representation learning, we typically try to learn useful representations for our data, with the ultimate goal for using these learned representations for a downstream prediction task (say, training a linear classifier on top). A good unsupervised learning algorithm thus learns to perform good compression of your data. We will now use the language of compression (over prediction).

A simple thought experiment

Consider two datasets

(You can think of

The gap between the LHS and the RHS is dictated by the shared information/structure present in the two datasets, or the algorithmic mutual information.

Okay, but how does this relate back to unsupervised learning?

Formalization

Consider a machine learning algorithm

Low regret = “we got all the value” out of the unlabelled data, and nobody can do better!

Kolmogorov complexity as the ultimate compressor

The Kolmogorov complexity of an object (this could be any data, really) is the length of the (or rather, a) shortest program that produces the object as its output. In essence, this is all the information you need to produce the output. If the program to create a 20MB image takes up 10 lines of code, then that program is a valid compression of your image. Taking this a step further, the following is true, for a (computable) compressor

While I won’t dive too much into this, you can reason about this better with the previous example of string compression. Let’s say we had no compressor i.e we’re simply storing the string in bits. Thus, if we had a

Right here, let’s pause, and let Ilya lay out a brilliant analogy to neural networks. Kolmogorov complexity is uncomputable for a general

Conditional Kolmogorov Complexity as the solution

We look at how conditional Kolmogorov complexity can be thought of as the solution we’re looking for in unsupervised learning. If

First of all, what does the conditional Kolmogorov complexity mean? conditional Kolmogorov complexity here is the shortest program that can output

Just compress everything

Some technicality on the conditional complexity mentioned above: instead of talking about “conditioning” on a dataset, where we’re talking about compressors that are compressing

This comes from the chain rule for Kolmogorov complexity. In words, this means that the shortest program that outputs

First, “generate” X, then “use” X to generate Y, and this can’t be too different from generating the two datasets jointly

Thus, you can now simply talk about the old fashioned Kolmogorov compressor, that compressors two datasets

Joint compression is just Maximum Likelihood Estimation

Ilya now brings up an equivalence between joint compression and maximum likelihood. Suppose that we have a dataset

Adding another dataset - or performing joint compression, is simply adding more samples to the summation above.

A key takeway here: Neural networks/Transformers are computers performing joint compression of all your input data samples through maximum likelihood, and we use SGD to search over the infinitely large space of possible programs that perform compression, and choose a sufficiently good compressor.

GPT

The GPT-N models trained by OpenAI can be understood by thinking about conditional distributions of text. During training, a causal language model like GPT is trained to perform next word prediction given a text chunk from some random document. By training over a huge, internet-scale corpus of such documents, these neural networks learn an internal model of different conditional distributions of text.

Is this universal across data domains?

Can this work in the domain of computer vision, dealing with images or videos? Ilya brings up research from OpenAI to argue that this does work.

iGPT

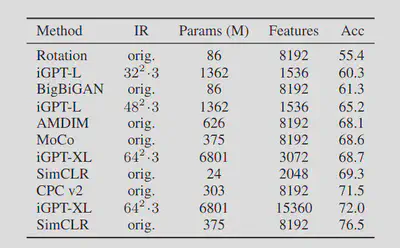

iGPT is an unsupervised transformer-based model trained on images. The data preprocessing is simple: They simply pre-process raw images by first resizing to a low resolution and then reshape into a 1D sequence. The model is trained to perform next-pixel prediction on these pixel sequences. Ilya now goes into more detail about the performance of iGPT across different scales, which I won’t talk about here. What is interesting, or important to note is that the performance of iGPT came pretty close to the best unsupervised models trained on ImageNet.

A comment on how linear probe accuracy is measured: iGPT and SimCLR provide a representation of the image - a good compression - and then a linear classifier is trained on top of this representation to perform classification. The accuracy of this linear classifier is the linear probe accuracy.

Limitations/ Unanswered questions

These are some limitations or unanswered questions that are not addressed from the above compression theory on unsupervised learning. I don’t want to expand this section too much, so I will simply list out the points almost verbatim from Ilya’s talk:

- Compression theory does not immediately explain why representations are nice and linearly separable.

- Linear representations are so pervasive that the reason for their formation must be very fundamental, but this is not captured.

- Auto-regressive (AR) models seem to have better representations than BERT-like models. Ilya’s speculation here: With AR models, you need to predict the next word/ pixel based on all the previous word/ pixels, and you need to look at the entire context. This is not the case with BERT-like models, where you mask out a certain percentage of pixels/ words and then look a bit into the past and the future. The hardest prediction task in next word prediction is a lot harder than the hardest prediction task in masked language modeling.

Summary

- Ilya delves into the mathematical and conceptual foundations of unsupervised learning, formalizing how machine learning algorithms learn from unlabelled data by capturing its inherent regularities.

- Compression theory can be used to explain unsupervised learning. There is a one-to-one correspondence between all compressors and predictors, and a good unsupervised learning algorithm needs to perform good compression of your data, to get good prediction on a downstream supervised learning task.

- Kolmogorov complexity can be viewed as the gold standard for compression. In unsupervised learning, we’re looking towards extracting as much value as we can out of some unlabelled data

- Neural networks are computers that can simulate different programs, and SGD is the handy search algorithm that we use to efficiently search over the infinitely large space of programs/circuits to get as close as we can to the optimal program (Kolmogorov complexity).

- The Generalized Pre-trained Transformers (GPT) models by OpenAI and their variants in other domains like computer vision (iGPT) are some real-world examples of unsupervised learning via the proxy task of next-token/pixel prediction. Next-token/pixel prediction has been shown to be a good proxy to learn the true, hidden structure in your data i.e to perform good compression.

- Some limitations of this theory are that it does not explain the linear representations we obtain from good unsupervised learning algorithms, and we also don’t understand why auto-regressive modelling is superior to masked language modelling in learning good representations.